An optocoupler, which is a creative combination of a transistor and an LED, is not one of the basic electronic components. It is not as common as resistors and capacitors, but it has found its niche in specific types of applications, mainly due to its unique design. Just as in a classic bipolar transistor, one of the terminals, called the base, acts as a pin controlling the current flowing between the collector and emitter, the transistor in an optocoupler does not have this terminal. The function of managing the flowing charge carriers is performed here by light, or more precisely, by photons emitted by an LED structure located right next to it. This type of design, although it may seem surprising, has one specific advantage. The transistor and LED circuits are galvanically isolated. This means that we do not need a common point, which is particularly useful in equipment where we want to separate low and high voltage areas. Thanks to optocouplers, we can control the current flowing on the so-called hot side with a small voltage that will control the LED. For this reason, optocouplers are mainly found in power supply sections.

A diode and a transistor – I don’t know about you, but I’ve always wondered whether the LED inside the casing really lights up. And if so, what does that light actually look like? Optocouplers are usually enclosed in a sealed, monolithic casing, but some time ago I managed to get hold of some interesting components that I hope will answer the question in the title.

Disappointing К249КП1

I had high hopes for the Soviet К249КП1 circuit. The examples you can see in the photo date back to 1989 and are designed for “surface” mounting. Inside this chip, there are actually two separate optocouplers, which are unique in their own way, because in this solution, one of the leads actually acts as a transistor base, even though it is controlled by the light of a diode.

These small metal casings are extremely easy to open. Their top “flap” is soldered, so a light stream of hot air is enough to reveal the interior of the integrated circuit.

This is what an optocoupler looks like, or rather optocouplers, because there are two of them. They are identical, so let’s focus on the one on the right. Here we can see two silicon structures connected to each other. The slightly larger one at the bottom is the transistor, with two leads, the collector and emitter, connected to external pins. What’s more, there is also a place to connect the base, left alone here. This fact is not consistent with the documentation, because, as I mentioned, according to it, the base should also be accessible from the outside, which, however, I have experimentally confirmed, is not true. For a moment, I thought that perhaps the transistor base was connected to the metallized layer at the very bottom of the structure, but this solution would not be a very good idea, because then we would connect both optocouplers. I also suspect that this transistor may be some kind of universal structure, also mounted as a single element and simply acting as a phototransistor here.

A small bead made of gallium arsenide and aluminum is placed on the transistor; this is an LED, whose light is controlled by the flow of current. The whole thing is held together with fairly strong glue or some kind of resin.

The GaAlAs compound suggests that the diode emits infrared waves, making it impossible to see with the naked eye. I conducted several experiments where a camera lens was pointed at the structure, but unfortunately no light could be seen. The structures are connected so tightly and the power of the diode is so low that we are unable to see it working.

Polish CNAP11 transoptor

In addition to the circuits from across the eastern border, I also managed to obtain a pair of CNAP11 transoptors manufactured by CEMI. This is a slightly more classic design with four leads, where a single pair of diodes and phototransistors is placed in a metal cap typical of the era.

In this case, getting inside is a little more difficult and requires careful manipulation of a mini grinder, but due to the fact that the interior has been filled with transparent plastic, the chances of everything surviving intact are much greater.

In this case, the internal structure is slightly different. A luminous structure has been attached to the bottom of the casing; it is a cuboid with a white top and black sides, visible here. The photons emitted by the diode hit the transistor structure, which is not visible in the photo and is attached to the metal L-shaped bracket above the diode.

In this case, the whole thing looked a little more promising, and I hoped that something would be visible, although here too we are talking about infrared light, which cannot be seen with the naked eye.

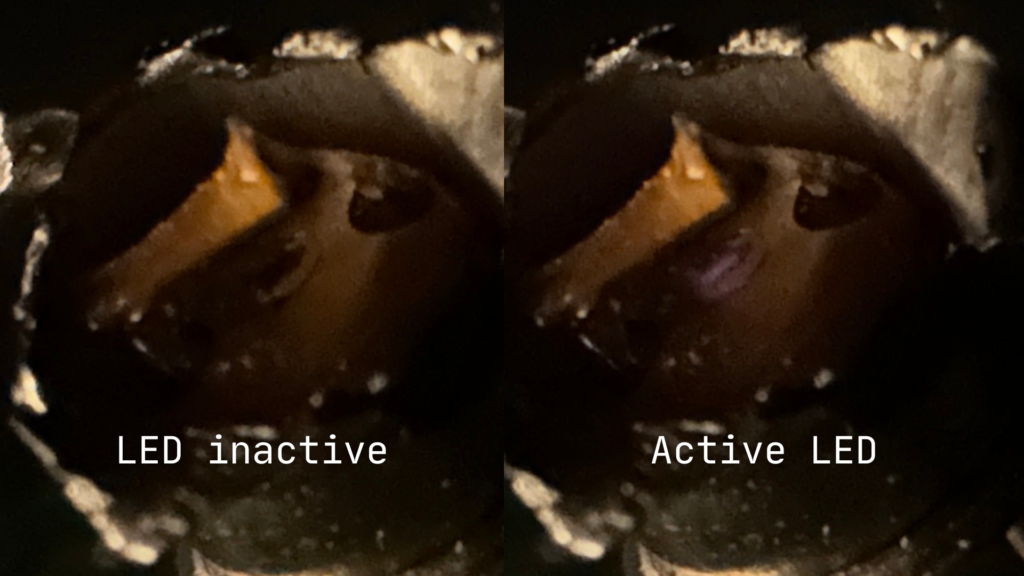

It was quite difficult to see any light, but I managed it. By setting the optocoupler in complete darkness with minimal glare so that the camera could focus, I was able to take several photographs of the LED lit and unlit. The difference is really minimal, but after applying the appropriate voltage, you can see a slight glow in the place of the silicon structure. This is the light that is usually sealed inside the optocoupler housing and controls the current flowing through the transistor.

A transoptor where you can actually see the light

An interesting historical fact is the component manufactured by Raytheon and designated CK2000. It is a truly ancient optocoupler, whose light can be seen with the naked eye. Inside, there was a classic light bulb with a silicon element. However, this solution was quite unreliable, especially due to the short life of the bulb, but at that time, before the invention of the LED, it was the only way to build optocouplers.

Sources:

- https://www.podzespoly-elektroniczne.pl/pictures/f52854cc99.pdf

- https://doc.platan.ru/pdf/datasheets/russia/K249KP1.pdf

- https://www.industrialalchemy.org/articleview.php?item=2043